This is an interview with Tom Maher (son of Rody Maher and Annie Buckley)

by Sister Pauline of St Joseph’s Convent, Kilmore, Victoria. The recording was made in 1978 and I transcribed it about 20 years ago.

Tom was involved with the Kilmore Historical Society and would speak to visiting groups of school children about early Kilmore, but when he got too elderly to do this Sr Pauline recorded an interview with him to use with the students.

Some parts of the recording were inaudible and Tom was elderly when the interview was done and so there are some gaps in the transcription.

SP: I’m just getting a project ready about Kilmore, Tom, and we want to see what you can remember about different things in Kilmore. First of all, where did the town get its name?

TM: There’s two Kilmores. There’s Kilmore in Ireland and Kilmore on the Isle of Skye, and my friends from Scotland didn’t know that until I told them. It’ s the Irish one that we got it from I think. It’s from Kilmore in Ireland.

SP: Does it mean ‘big church’?

TM: Yes, and of course the first church here was St. Bridget’s that was out in Willowmavin and it was on a property that the Aherns had. There’s only the remains of it now. There’s just a heap of rubble and mould and a few old bluestones just to show where it was. I believe that the first mass here was celebrated by a priest going through on a property that Tom Sheehan had, it was then a hotel called …

SP: Doesn’t matter, you’ll think of it later. How many hotels were here, Tom?

TM: It was reputed that there were 52 in the district.

SP: How many hotels here?

TM: Officially it was 32, but then there was shanties all over the place. Where Dr Jayne recently came from up there in the new township, Powlett Street, that was the shanty on the road. It was only road traffic, you see, there was only tracks through here, there was no main road. And they went through about three different directions, three different ways that I can remember of anyhow, that I knew of. Eventually then when the main road opened up … Kilmore wasn’t intended to be built here at all on the situation where it is, it was out at Lake Logie, and there was only one building put up out there. Then as the people with the horses and the wagons came through the town, through what is the town now, they pulled up to water their horses down behind the post office. And as they did there were different places started to pop up and the result was that the town never went out to where it was originally intended by Rutledge, out to Rutledge’s survey. And that’s where Rutledge Street gets its name. As Kilmore got the butter factory there, the manager, Mr J.D. Ryan, he’s pointed out to be about 40 different farms around Willowmavin supplying milk and cream to the factory. But, as the families got larger they had to move on, the population was too big they couldn’t keep up to it. So Gavin Duffy was our Member of Parliament at the time and Kilmore East was known as Gavin Duffy Town and why they changed it I don’t know. But he was the Member of Parliament at the time and he brought in what was known as the Duffy Act and he opened up all the Goulburn Valley to settlers at pretty cheap rates and they started to expose people to the land and that’s why up around the Goulburn Valley and those areas Kilmore was so well known and everywhere you went the people knew of Kilmore. And all over Australia really. One chap recently I knew on holidays, he went up to Queensland, and he remarked he came from Kilmore, and this chap said ‘that’s where they have the trots and the races’. Kilmore is known everywhere, no matter where you go you’ll find somebody that knows somebody or something about Kilmore.

SP: Of course it’s very famous for Ned Kelly was born around here. Tell me what you can remember about Ned Kelly.

TM: Ned Kelly was born at Beveridge, only about a mile from where the old Beveridge church is now. He went to school, or whatever schooling he did (it wouldn’t be much at the time). But Kelly weren’t a bad fellow – he only did what most lads of the time did. They’d often take a horse that was there staying around the village for the night. And they’d plant it in the trees, hide it, and then in a day or two there’d be a pound reward or something like that, and they’d bring it out. Well that was the only thing they done. It was really the fault of the police that the Kellys went out. They were coming around and they were making a nuisance of themselves to Kate Kelly and Mrs Kelly, and one of them went to molest Kate Kelly and Mrs Kelly hit him with a shovel and then the police were down on them all. That forced the boys to go out. When they went out on the road, as they called it in those times, they were well looked after by all the people, because whatever they took – they didn’t take anything for themselves, and whatever they took they gave to the poor people. The banks they held up at those times, Jerilderee and Euroa, they never hurt anybody or done anything wrong in that way. In fact I’ve got a gun here that belonged to my brother and that was Sergent Kennedy’s gun who was in the affair at the Longback Ranges, where one of them was killed.

SP: That was Sergent Kennedy.

TM: Yes, it was Sergent Kennedy’s gun, and it was given to my brother. It’s still here, have you ever seen it?

SP: I think you showed me, yes.

TM: When they were on the road they never done anybody any harm. And this friend of mine who had a property out at … he was a hawker. He saw them and he knew they were in the district. He though when he saw them coming up the road ‘Well this is it, I’m going to be stuck up now’, but to his surprise they just pulled up and asked him if he had any tobacco. He said ‘Yes, how much to you want’, he said. They told him and he gave them what they wanted, and they threw him more money than paid for the tobacco.

A friend of mine and my father’s was a young man, he was only 16 when he went up around the Dookie area breaking in horses. There was a lot of horses tied up around the Ryan’s shanty. He was paying attention to one, looking at it, and a chap said to him ‘You seem to know that horse laddie’ and he said ‘Yes I think I broke that mare in for Tom Ryan’. He asked him in for a drink. He didn’t say he did break her in, he said he may have. So they went in for a drink, and Kelly, asked for a strong drink. The other fellow didn’t know what to ask for and he said ‘I’ll have the same’ and he said ‘No laddie you won’t’ and he got him a soft drink. And he didn’t know until after they’d gone that that was Ned Kelly that he was speaking to.

SP: And what happened towards the end of his life, Tom?

TM: No, it was all up around Glenrowan. There was a school teacher from Romsey was the man who tried to flag the train down, when they took the cannon on the train to Glenrowan when they had the shootout. It was reputed that there was a portion of his armour made here in Kilmore, at the old blacksmith shop, where that was, it’s demolished now, about three miles from here. I don’t know whether that’s correct or not, but it was reputed that the armour was made in different places.

SP: Now, Tom, your brother was a blacksmith. Tell us about him and how he started.

TM: He started working in … in the depression times and he worked very hard. He was taught by a man who was very good and he showed him a fair bit. He was such a good shoer that he was offered a job by the Victoria Racing Club as chief in charge of shoers and blacksmith on the racecourse. He done very good work with trotters. There was a horse over here from Sydney, he came over he accompanying another horse as a foal, and they brought him over again when he was racing. They had difficulty in getting him shod properly. Anyhow they got my brother to do him, and he went down to Flemington and he won the race. They offered him a trip to Sydney for a week, pay all his expenses and everything, and my brother declined. He was going over to the show, and I thought he was foolish, he didn’t take his gear and do the horse but he said he was on holiday and he didn’t want to do it. But he’d been a successful blacksmith here in Kilmore, he’s known practically all over Victoria.

SP: Is he still working?

TM: Yes, he does a little bit just to keep his hand in for friends who were good customers of his years ago. He leased the shop to another chap, but he doesn’t look after it, he just turns up occasionally, doesn’t work it at all. But my brother can’t get out of doing jobs for people who were good customers years ago.

SP: Yes. Tom, tell us a little bit about Whitburgh Cottage – that historical cottage. Do you know anything about that?

TM: The people who started that, Mr Smeaton, he came here, going through like a lot of others at the time. He pulled up on the corner of Powlett Street and … that’s right on the main road. He started doing a few jobs there and he eventually bought the property from there right up to Melbourne Street corner. He started on getting Whitburgh cottage built and he got one portion done first, and then added to it later.

SP: How did it get the name, Tom?

TM: I should think it might come from the Scottish people – it might have been a name from over there. There were Mrs Smeaton and the sons, and Mrs Smeaton reckoned that when she got the stove in the back portion … First of all, they had a kitchen, and they had what’s called a crane and they hang the kettle or whatever they’re cooking with on this crane and they swing it in and out. Mr Smeaton made this crane himself, and I think it’s worthwhile if you ever get the chance to go in and see it when it’s open on Sundays, and ask to have a look at this crane. He’s made it himself. I have a crane in my back yard, it’s not erected of course. This one of his has rather great workmanship because it can be raised or lowered as you wished. Most of them had a chain hanging down and they’d just work it on the chain, lower or higher the article they’re cooking in. When Mrs Smeaton, used to cook in a camp oven of course, then when she got the stove she reckoned she was made, you know. Whitburgh Cottage was eventually procured by the Historical Society, and it’s well worth a visit, especially for anybody who knows much about the earlier days.

SP: Tom, you tell me that you used to go down to Melbourne by horse, how long ago would that have been, do you remember?

TM: Well, when Mrs Morrissey was in hospital, she had a broken leg. Her leg was broken as she was coming home from Kilmore East after taking Mr Morrissey down to the train. She was in Koonara (?) Hospital out in St Kilda Road. It belonged to the Quinlans from Yea, and some of them had connections around Kilmore. We used to go down to see Mrs Morrissey on weekends, and we’d go down from Kilmore on the Saturday afternoon and go right into the centre of the city to the City Club Hotel.

SP: Was it horse or horse and buggy, Tom?

TM: Horse and jinker, and we’d stable the horse there. We’d get from here to right into the centre of the city in three and a quarter hours, and it was good for those times when you come to think of how it would take you that long to drive it sometimes in the traffic now. On the Sunday morning, rather than have the horse standing in the stable all the time, just on the hard bricks or whatever, we’d go in and get her and we’d go for a drive to where the shrine is now. We’d come back, put the horse away, feed her up, then on the Sunday evening after the evening cooled off (it was generally in the summertime then) we’d set home for Kilmore.

SP: What sort of roads were they, Tom, were they bitumen?

TM: No it was all metal roads. They called it McAdam, after McAdam the man who invented it, McAdam, a Scotsman. And we’d drive home to Kilmore.

SP: What year approximately would that have been, Tom.

TM: Somewhere about 1920. Whenever they were short of a driver for one of the fruit wagons, Mr Portbury’s father owned the business then (Mr Portbury’s still in Kilmore), they’d come and they’d get me. Mr Ashton used to drive the wagon with two horses in it and I’d drive one wagon with one horse in it. We’d take all the empties to Melbourne on Monday and we’d stay in the hotel, the Royal Saxon on Monday night, get up about two o’clock in the morning, Mr Ashton would do all the buying, and his daughter is married to my brother, Toc, the blacksmith. We would then load up and be ready to leave the market about 7 o’clock, and we’d set home for Kilmore. It was a big long drag all loaded up with vegetables. We’d get home to about Wallan that night and we’d stay at the Inverlochy Castle Hotel, it’s now demolished, there is a few remains showing where it was. The reason why we stayed that night was that Pretty Sally was a stiff hill in those times, and it was too much on the horses after the long drag from Melbourne to face the hill. So we’d get up early on the Wednesday morning and come into Kilmore. That was your fresh vegetables. And now – later on my two boys used to go down with the man that went down from here in a motor vehicle, go to Melbourne, leave here about midnight, go down, and they’d get the vegetables [and return] in the same morning. A bit of a difference to the times then.

SP: Tom, you were connected with the racing club. Tell us how it began and remember about it.

TM: Kilmore Racing Club was established long before Flemington. We had a few meetings and we had the Hibernians, of which I am a member, we held race meetings every year. The Hibernian race meeting was known as the Kilmore Steeple Chase and it was run over four miles. The big fences that were there then when I was a boy weren’t used when I was a boy, they were finished with but they were still remaining on the course. There was a low fence, paling fence and post and rail and a water jump (there were only two in Victoria, one in Flemington and one here but Flemington was later). When I was a boy Mr Morrissey always had an interest in a racehorse or two and I started looking after them as well as helping him in the shop. Of course I got riding horses on the track, and very keen on it. I was working at the racecourse by that stage, actually I worked 60 years without missing a meeting. I missed working one meeting because of an operation, but I was present at the meeting. I worked 59 out of the 60.

SP: That’s a great record, wasn’t it?

TM: It was mostly honorary those times. I was 44 years Clerk of Course, which is a record for Victoria so far, and mostly without any pay. Until one fellow was paid one time and the other man wasn’t the day I was on, and he jacked up on it and I was offered payment the next time.

SP: What was the duty of the Clerk of Course?

TM: The next day this chap, the secretary said to me, you can take pay if you like or you can give it back as a donation. I said that I’d let the other man go first and if he takes it I’ll take it. He took it and I took it and I’ve taken it ever since. The duty of the Clerk of Course, and the coat that I wear, or did wear is now about a hundred years old. My brother has a whip that belonged to the man that gave it to us, and it’s the same age. It was the whip of the hounds. There were two packs of hounds in Kilmore – a public one and then there was a private pack. The Clerk of Course gets the horses out of the stalls and into an assembling yard, takes them into the mounting yard, and takes them out of there down to the start stalls, or in my day that was an open barrier, and then the stalls came into being. Sometimes there would be nine races and you’d have to do it all on your own. Later on the VRC brought in a rule that there had to be two. I was so keen on the horses and being with them so much that I became an amateur rider. I rode in the central districts of Victoria, and I won the main amateur riders’ race in Victoria twice. During my time of riding, amateurs were not supposed to take money but they did. I found out some of the others did. But I never accepted a penny for riding from anybody, and I never during a race pulled a horse up for anyone, nor did I hit a horse. I got roasted a couple of times for not hitting, but I realised that when a horse was doing it’s best, there’s no point hitting it. As a matter of fact I was told, accused, by the police one day of pulling a horse up and I was trying for my life. He didn’t know that if I hit it, it would have stopped. It was moving at the time. It was a pony called Palaco, his father was Stickup and his mother was Clobber and he was called Palaco. If I’d hit that horse it would have lost – instead of losing by about a head or half a head he’d have lost by a length or more. I had a great time riding around the country … I would say this – that I am one of the only riders who rode against women in races. That happened at Kilmore and Pyalong. The most famous of them all was Mrs Murray who lost her life trying to save Garryowen. They both got burnt, and that’s why the Garryowen trophy got its name.

SP: Tell me, the coat you were talking about, do they still wear heavy a one like that?

TM: No, they don’t. They have a shorter coat. But the one I have is really outstanding as regards to work on it, you know, needlework. I tried to get one one time, but I couldn’t get one from around Australia at the time and I couldn’t get one from England. But it was a heavy coat, it was heavy in the summertime, but in the wintertime it withstood a lot of rain. To my knowledge there was only one man ever killed here at Kilmore in a race.

SP: Kilmore is one of the biggest racing places in Victoria

TM: Yes, racing and trotting. As a matter of fact I’m just reading now about the pacing cup coming up. It’s worth about thirty thousand dollars, trophies and a motor car, things like that … jewellery, things that are given to the owners of the winner.

SP: Tom, can you remember anything about that old gaol, down there near the state school, it was a gaol wasn’t it?

TM: It was a gaol. Some people would say that Kelly was in it, but he was never in it – his father was. It was only a gaol for about eleven years I think. It was sold then and eventually it was made into a butter factory. Mr J.J. Ryan, Geoff Ryan’s father – he was the manager and then he bought it, and it went for quite a few years. And then a — bought it and they were going to extend it — put all the men who were working there out of work.

SP: What about that monument?

TM: The monument up there, I had a lot to do with that. That was a sentry tower from the gaol and it was situated approximately behind, between the Presbyterian Church and the gaol. It was about fourteen foot six high and about six foot six square. There were windows to look out and you could go to the top of it. It was taken up there by volunteer labour. As a matter of fact the road that it was taken up on was built by soldiers after the First World War. I know very well because I carted the shovels and picks and things to them working on it. I know some of the men who worked on it, and they’ve gone now, those fellows. There were three men worked on that job, farmers and different ones. Mr Clancy was one of them, he carted material up. It was taken down brick by brick, bluestone by bluestone. It was marked, I don’t know how, and it was re-erected up there and used as a Hume and Hovel memorial.

SP: Did they actually pass over there?

TM: No they didn’t pass there, they passed nearby. The plaque is on the front. A few years ago when I was more active I used to go up there and keep it clean. It’s always messed up by vandals, rubbish around, and a target for bottles and things like that, even rifle shooting. The girls used to come up with me and clean it up. We did put a container up there but they used to empty the containers and make a mess around. Eventually we got the council to put up a very good container on a post and bolted and the vandals cut that padlock, and the beautiful drum that was there, that was taken.

SP: Senseless isn’t it? Can’t understand it.

TM: Some of the drums that we’d gave there had been rolled down the hill towards Kilmore East. I took lots of visitors up there and from that point you can see right up through to Bendigo, and you can see at the end of the ranges Mt Disappointment, right across to Mt Macedon. Everybody reckoned it was a wonderful view. Pretty Sally of course, you can see the traffic going along the main highway.

SP: What about that Mechanics’ Hall, Tom, what do they use that for?

TM: That’s not to be used.

SP: No, but it was used.

TM: It was used for years and years. I knew it had a library in the back but there were some great entertainments, dances and concerts and things held there. I won a competition there one time in bed-making.

SP: Good heavens, how did they do that?

TM: They had single beds there and they had the clothes to put on. Another thing I won there was a ladies’ hat dressing. I was pretty lucky I got an easy one to do and then you had to wear the hat. I was pretty lucky in sporting events.

(END OF SIDE A)

…that was built after St.Bridget’s, I suppose, in Willowmavin. When we were at St.Bridget’s there were about seventy-five pupils there.

SP: Who taught in it, Tom?

TM: I couldn’t tell you now.

SP: Not nuns or brothers.

TM: No, I don’t think so. I first started school in 1908 where you are now. That was just after my mother died. There was four boys. My father had a small property out there and we came into the town and he took on the mail contract from Kilmore to Lancefield. That was three days a week by horse drawn vehicle. We had to walk to school in those days, there were no buses or no school buses, no rides, nobody came to pick you up when it was wet. When my two boys started school Sr. Barbara, now Sr. Pauline taught them at school. After my mother died I went down for a while with my auntie to South Melbourne. I went to the nuns there for a while. My cousin stayed with my father and when he wanted to go to Melbourne to work, he was an apprentice saddler, he went down there and I came back home.

SP: What about that little brick place that used to be a school up near the church, Tom, wasn’t there a school up there?

TM: The bluestone, that was the old school that I went to there – two big rooms.

SP: Is that where you started or where you finished?

TM: No, I started down there … [meaning St.Bridget’s]

SP: … at the convent, and then the Brothers had that building, I see.

TM: The sisters were in the big buildings where the College is now, and later on when the changeover came the brothers had the buildings and they also had what we call the St.Pat’s – the bluestone buildings, two big rooms.

SP: Tom, tell us what you remember about Hume and Hovel.

TM: Hume and Hovel set out from Sydney or thereabouts to try and find Port Phillip or Westernport Bay. They travelled across country. The first I can remember of them was Mansfield and Euroa, and there’s camps at the different places showing where they passed nearby. That’s why the Hume and Hovel monument is built there because they didn’t pass close by but they passed within tow or three mile of it. Wandong, I believe, was called Hume’s Gap and I don’t know why they changed that. Anyhow they were criss-crossing as they travelled along. They crossed one creek on a Sunday and they called it the Sunday Creek, and it’s still known as the Sunday Creek. It flows into the Goulburn. They passed another creek and it was dry, there must have been a drought because they called it the Dry Creek. There were two Dry Creeks that I know of, there was the Dry Creek near Kilmore East and I’ve only known it to stop once. The other one is up in the mountains. As they were travelling along they got to the top of the mountains where we get our water supply from and they travelled along to the end of it. They should have been able to, with their … glasses, to have seen the Bay or Westernport Bay. It must have been a hazy day because they couldn’t see it and that’s why they called it Mt. Disappointment. They crossed from there to the hills just below between Beveridge and Wallan. They climbed that, and they couldn’t see anything from there and they headed out across country, and they came out at Corio Bay. They called one creek there that is now known as Hovel’s Creek and you’ll see a cairn or two along the road as you go down that way, if you’re going to Geelong. They weren’t very far out in their estimations after all that distance to get so close to Westernport Bay as what they did. I can’t remember much more about that.

SP: Can you remember the names of any other places that were named after the

SP: Where did Burke and Wills go Tom?

TM: No, I don’t know. There was a lot of timber brought in from the Mt. Disappointment area and it was cut up on the saw-mills out there. After the disastrous bushfires of 1939 they brought it in the logs and milled it in Broadford. Every other town was the same, they had to have dugouts and things like that. In fact my cousin was working at the mill and he was on holidays, and every one of his mates got burnt to death. He was brought back to try and identify them. I had a friend, she got so hot, she got into the waterhole, the dam that was near the house. The water got so hot they had to get out of it.

SP: Tom, can you remember how the priests used to travel in the early days?

TM: By horseback?

SP: Do you remember any of the priests?

TM: No.

SP: Was that around your time?

TM: They travelled fifty kilometres to get to Lancefield and Baynton. I think I might have a book on it or something there …

SP: How far, what radius would they have come? Lancefield would have been the furthest, would it?

TM: No Baynton was further. They used to say masses in private houses out in … places like that, the outlying places. They travelled in horseback. Then when Fr. Martin got the motor buggy, when we were kids, sometimes we’d have to give him a push up the road. The noise, you could hear it rattling, it used to frighten all the horses about the place. Tommy Kelly was driving it, he was the altar boy who worked around the church, rang the bell, which is not ringing nowadays, he rang it twelve, twelve, six or twelve and you could set your watch by that. You could hear that bell – I know that I’ve heard it about nine miles out. He was going with Tommy Kelly to say mass at Darraweit Guim when the motor buggy was a bit top-heavy and it overturned. The steering wheel pinned Tommy Kelly down and Fr. Martin got away. He tried to lift the motor buggy off him. He could only ease it but it weighed so much he had to let it down again and Tommy Kelly was killed. He is buried in the Kilmore cemetery.

SP: What relation was he to Tommy Kelly that we’ve got? Is Tommy Kelly related to him?

TM: No, no relation. Fr. Martin became Dean Martin afterwards. He was our parish priest. He reckoned he’d never have another motor vehicle, but of course as time progressed he’d be like everybody else and get another one – a motor vehicle.

I remember an old couple who had a building that’s on the corner of Rutledge Street and Powlett Street – it’s on the south side. Cregans was their name, they were an Irish couple. He was a bootmaker. When the First World War was started, he read it out of the paper. His wife said to him, ‘Oh John wouldn’t it be a terrible thing if the Britons invaded Australia’. Another old lady, she used to ask us as we were coming from school how the war was going. I Kilmore we had about twelve or fourteen cadets, and they were only school age. One of those kids was a bit of a wag and he said ‘oh, the Germans are out at Bylands’. She said ‘Oh, the cadets will stop them’. The brothers had a boat up on the reservoir. The chain was broken.

SP: Tom, tell me something about the hospital, was it always there?

TM: Yes it was, as far as I know it was. One of our priests, Fr. Clarke was one of the main ones I think that started getting a hospital started here in Kilmore. His name is on the memorial ward up at the hospital now.

SP: Wasn’t there a priest that had his hand blown off in some accident?

TM: Oh yes, I was coming home from Melbourne. I was riding a horse down the road and poor old Fr. Gleeson, he was a very … man Fr. Gleeson. He had a detonator and he had a nail or something and he was prising it and it blew off and blew his hand off.

SP: And there was something about his journey to Melbourne, who took him down?

TM: I don’t know who took him down, but I drove the first ambulance in Kilmore. It was a horse-drawn ambulance, no motor vehicle, I couldn’t drive one then. But every time anything would happen the police would come down and get me. I’d get nothing for it, it was a thank-you job. I’d have to drive this horse that was kept at the livery stables.

SP: Where was that, Tom?

TM: Down where Putkers Bakery is, and next door was a photographer’s. there was about five blacksmith shops and a goat … and a coach painter when I was young, and four or five bakers. You could get a loaf of bread for eleven pence those days.

SP: What about the fire brigade, Tom, were you connected with that?

TM: Yes, I was twenty-five years in the fire brigade. I had a long-service medal for that.

SP: And was that a horse-drawn thing too?

TM: No, it was manpower. We’d be generally knocked-up by the time we got there, and the water would hardly trickle through the hose.

SP: Why couldn’t they get a horse to pull it, Tom?

TM: We did when … came about. We tried sitting in a motor vehicle and holding it and dragging it that way, but it was so fast it nearly rattled the wheels off.

SP: But why didn’t the have horses?

TM: It would mean somebody keeping a horse and looking after it all the time.

SP: And how many men would pull the …

TM: However many turned up. There could be half a dozen of us or more. It had ladders on it, and it had buckets on it – little buckets they were.

SP: How much water would you carry?

TM: No water, you just had to take a chance on what was in the …

SP: How would they manage about bushfires and things like that?

TM: I saw my father and others go out to a bushfire and they had to break branches off trees and do the best they could. And by the time they got out to a bushfire, it had gone miles. One fire I remember, it went right down to Darraweit Guim and then the wind changed and it came back right alongside the same area that it went down. Things were difficult then. If you got a wet bag, if you were lucky, it’d soon dry from the heat. They’d only break branches and beat it as best they could. Things have changed now.

SP: Yes, they certainly have.

TM: I’d forgotten some things that I’d like to tell you about. I hope you’ve enjoyed these few words I’ve had to say. When I was fit enough to go round with you and some of the girls, I really enjoyed it. They seemed to enjoy the talks and whatever I showed them. So I wish you all well and hope you are obedient at school. So goodbye, Tom Maher.

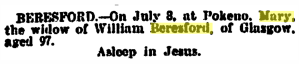

Notices, Headstone and Obituary: Margaret Theresa Maher

Notices, Headstone and Obituary: Margaret Theresa Maher Place Note: Springfield, Goldie & Forbes

Place Note: Springfield, Goldie & Forbes In loving memory of our mother Margaret Theresa Maher

In loving memory of our mother Margaret Theresa Maher