Many hardworking, law-abiding ancestors have lived their lives leaving behind a sparse and unremarkable trail of records, and often no images. My great-grandmother’s brother Leo Albert Worthington was not one of these people. His criminality spread over thirty-five years and at least eleven aliases.

I’ll start by saying that Leo was not a particularly good criminal, as his arrest record seems to show.

I’ll also state from the outset that even though Leo’s family life was rough and poverty-stricken, this is not meant to provide excuses for Leo’s actions, only to provide some context for his life.

He was born on 26 September 1893 at Forbes in central New South Wales to John Joseph and Mary Ann Worthington. He was the ninth child of eleven children. As the drought and depression of the 1890s set in, John Joseph lost his farm at Moonbi and the family moved into the Forbes township and he took work as a contract labourer. When work opportunities dwindled in 1900 he left the family, going north to seek work and was never seen again. Mary Ann went to the police in 1903 reporting him missing and a warrant was issued to no avail. She stated that she and the children were left destitute.

Mary Ann took the children to Cobar where her mother lived. Here the family were subject to a number of sad events, one being that on 4 Apr 1905 Leo, aged only 12, was convicted of stealing goods from a railway carriage at Cobar and was sent to the Carpentarian Reformatory for Boys for three years.

The Carpentarian Reformatory was established at Brush Farm, Eastwood, NSW in Sydney’s north west. It was named after the philanthropist, Mary Carpenter. At the time Leo was sent there it was run by the State Children’s Relief Department.

A year before Leo got there, the annual report of the Reformatory was reported on in the Goulburn Herald:

THE CARPENTARIAN REFORMATORY. THE CARPENTARIAN REFORMATORY.THE annual report of the superintendent of the Carpentarian Reformatory, Mr F. Stayner, has been received by the Minister for Education. Dealing with the way in which inmates are recruited, he says they come to the institution from the various police courts, quarter sessions. and so on for minor offences. Instead of sending them to jail, the magistrate orders them to the institution for not less than one year and not more than five years. Sometimes, however, the lads are not allowed to remain for a year, and no impression can be made on them in less than the time named, and nothing taught them in less than two years. Truancy and wandering in the streets also furnish their crop of recruits to the reformatory. Several trades are taught, such as tailoring, joinery, boot-making, and so on, and the boys are also employed in gardening and orchard work. Out of 361 boys who have at various times been discharged from the institution, 83 per cent have turned out well. (Goulburn Herald, 1 April 1904, p.5) |

Leo was unfortunately not to be amongst the reformatory’s success stories.

If he was released after the three years was up, it would have been a month before the death of his grandmother aged 85 at Cobar, but there is no evidence that he returned to Cobar. In fact, it’s hard to pinpoint where he was until his next convictions in May and June 1914 in Sydney for drunk and disorderly, stealing from the person and indecent language. His sheet has him as a labourer from Forbes who was born on 23/07/1893.

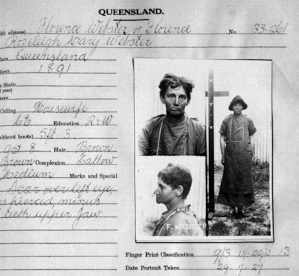

By this time he was aged 21 and had the tattoos that would appear beside all his mugshots ‘pierced heart inside left forearm and woman’s head outside right upper arm’.

At some stage, Leo’s mother contracted tuberculosis and from September 1914 until March 1916 she was a resident at the Waterfall hospital for consumptives. She succumbed to the illness on 20 March 1917 and Leo’s name was left off the family notice in the newspaper.

In the meantime, in 1915-1916 Leo was racking up convictions at Molong, Crookwell and Sydney, mostly for bad behaviour and violently resisting arrest.

Two months after his mother’s death, on 8 May 1917 Leo, aged 23 and apparently a shearer, enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force, 1st Light Horse. Though the lives of soldiers were difficult and dangerous, for young men with few prospects, enlistment in the armed services could provide an opportunity to break out of a cycle of crime, to travel, to be a part of something, and two of his brothers had already enlisted. However, Leo was discharged on 28 Nov the same year because of his criminal convictions.

In August 1917, before he was officially discharged, he was convicted in Sydney for two charges of shop breaking for which he received a sentence of two years. His sheet says he was a labourer from Forbes who was born on 23/07/1893.

After release (and before his prison haircut had had time to grow out) in October 1919 he was charged in Sydney with unlawfully wearing a military uniform and a month later with shooting with intent to cause grievous bodily harm, for which he was sentenced to 12 months. He used the name Edward Vivian Miller and said he was a wool classer from Orange born 3/8/1894.

On 9 November 1920 at Maitland Quarter Sessions he was convicted for breaking into a warehouse and stealing goods valued at £300 and sentenced to four years penal servitude. His sheet has him using the name Edward Mullins, a labourer from Forbes born on 01/08/1893.

After release, he was charged in May 1924 with attempting to break into a shop with intent to steal. He absconded after release on bail. He finally ended up at Sydney Quarter Sessions in May 1926 and was sentenced to three years hard labour.

In 1928 his photo was retaken for some reason, and he doesn’t seem very healthy.

Upon release, Leo ended up in Victoria where he was convicted of shop breaking and sentenced to 12 months. He used the name George Monaghan, and said he was a native of Victoria born in 1893.

Having pleaded guilty to a charge of shop breaking, George Monaghan, who said that his correct name was Leo Worthington, aged 36 years, shearer, of Gertrude Street, Fitzroy, admitted 14 previous convictions, mostly in New South Wales.He had served a sentence of imprisonment for 12 months for shooting with intent to do grievous bodily harm and a sentence of imprisonment for four years for shop breaking. Having pleaded guilty to a charge of shop breaking, George Monaghan, who said that his correct name was Leo Worthington, aged 36 years, shearer, of Gertrude Street, Fitzroy, admitted 14 previous convictions, mostly in New South Wales.He had served a sentence of imprisonment for 12 months for shooting with intent to do grievous bodily harm and a sentence of imprisonment for four years for shop breaking.

Judge Moule said that on the occasion which had given rise to the charge nothing of much value had been stolen. Monaghan would be sentenced to imprisonment for 12 months. He would also be declared an habitual criminal and would be detained in a reformatory prison at the expiration of his sentence during the pleasure of the Governor. |

I’ve given an overview of some of the crimes that caused incarceration on the occasions of his photographs being taken, but his petty criminality extended well beyond these charges, and finding all reports in the police gazettes to put together a timeline was like untangling a ball of sticky wool. Apart from Edward Vivian Miller, Edward Mullins, James Rands and George Monaghan, he used the aliases Joseph Downey, James Downey, Ernest Sergeant, James Mitchell and James Cavanagh. It must have been a very difficult job for the police to match up descriptions of offenders trying to evade detection by giving false information. Additionally, many of his cohorts had numerous aliases. Fortunately, each prison portrait sheet contains all the known aliases and all the previous photograph numbers so it’s relatively easy to collect the set.

The online criminal photographs go up to 1930, and when further records go up there will be at least two more photos to add to the gallery from the next decade.

In March 1933 Leo was sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment for having stolen a silver watch and chain from a man in the street in Sydney. He was convicted under his own name and was recorded as a 41-year-old labourer.

In 1934 he was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for possession of an unregistered automatic pistol at Redfern. Ballistics testing on that pistol revealed that it was a match for a casing found at the scene of a shooting that had occurred at Glebe four days before the gun was recovered.

Arthur North of Glebe had initially told police that he had found the gun in an alley at Redfern nine months before he was shot in the leg, that it had accidentally gone off while he was looking at it, and that he had given it away before police arrived at the scene.

When Leo’s involvement was unearthed by the ballistics, he said that he had taken the gun to North’s house, and that he was showing North how to use it when it accidentally went off, and that he had fled the scene and called an ambulance. The story was corroborated by North and accepted by the magistrate.

In police circles, the case is regarded as being of considerable importance in that it established a precedent for the legal acceptance of ballistics photographs. Science had proved that both shells had been fired from the same weapon and the proof was corroborated — if proof can be corroborated— by the dramatic admission of Worthington that the shot which wounded North was fired from the identical pistol. In police circles, the case is regarded as being of considerable importance in that it established a precedent for the legal acceptance of ballistics photographs. Science had proved that both shells had been fired from the same weapon and the proof was corroborated — if proof can be corroborated— by the dramatic admission of Worthington that the shot which wounded North was fired from the identical pistol.(The Truth, 8 April 1934, p. 19) |

I don’t believe that anyone else in the family has ever made a contribution to forensic science but, apparently, The Truth thought Leo did!

In June 1939 he was sentenced to three years imprisonment for assault and robbery at Maroubra in January that year.

After the expiration of this sentence, things seemed to settle down. In 1943 Leo was living in Bourke Street, Surry Hills and is recorded as a labourer in the electoral roll. In 1949 he was living in Toowomba and is recorded as a labourer.

In 1951 he married Rose Ann Mitchell Cuddy (nee Teague) at Toowomba. He was 58 years of age and Rose Ann was 75. In 1954 they both appear in the electoral roll residing in White Street, Everton Park, a suburb of Brisbane.

Rose Ann died in 1956 aged 79 and was buried at Lutwyche Cemetery, Brisbane. In 1958 Leo was living at 139 Latrobe Terrace, Paddington, an inner suburb of Brisbane, and working as a salesman.

Leo died on 26 Feb 1961 in Brisbane Hospital of heart failure, the culmination of heart problems he had apparently been suffering with for about 12 years. He was buried with Rose Ann at Lutwyche Cemetery.

Leo’s youngest brother Eugene Henry (‘E. Worthington, brother, 68 Albany Road, Stanmore, Sydney, New South Wales’) gave information for his death certificate. Interestingly, Gene gave their father’s name as Leo Albert Worthington.

Unsurprising that Gene would be hazy on his father’s name, as he hadn’t seen him since he was four years of age. Leo’s passing left Gene as the only living child of the family.