Glen Huntly (1840)

Glen Huntly (1840)

Departed: 14 Dec 1839 – Geenock, Scotland

Arrived: 17 Apr 1840 – Port Phillip, Vic.

Master: Captain John Buchanan

Particulars: 505t barque ; travelled via Oban

Notes: Eighteenth of the original Bounty Scheme ships ; 157 passengers including 25-year-old Alexander McKenzie (‘Black Sandy’) and his cousin, also named Alexander McKenzie (‘Red Sandy’). The nicknames distinguished the cousins by hair colour.

John O’Groat Journal, 16 August 1839, p.2

The beautiful new barque, Glen Huntly, Captain Buchanan, launched from Mr Bremner’s yard here, left Poulteneytown harbour on Friday evening, and was towed out of Wick bay by the steamer Sovereign. The Glen Huntly has a very fine appearance on the water, and from all we can hear, fully justifies the most sanguine expectations which were formed of her.

… We have been informed that the Flamer of and from Liverpool, for the Baltic, sunk off Barra Head on the 6th instant, having previously struck on a rock. The crew were saved by a Danish brig, and landed at Westray. Three of the men came here, and shipped themselves board the new barque, the Glen Huntly.

Inverness Courier, 6 November 1839, p.2

The splendid ship Glen-Huntly, which sailed a few days ago from Greenock to the West Highlands, for the purpose of taking emigrants on board for Sydney and South Australia, has struck on the rocks near Skye, and will be obliged to undergo repairs. The cabin passengers, we hear, will be taken out in the Tomatin, which is lying at the tail of the bank at Greenock, ready to sail for the same destination. This accident will be a serious loss to the poor steerage passengers, who all waited for embarkation after having parted with house and home.

The Herald, 26 Feb 1884, p.3

The Chronicles of Early Melbourne : Historical, Anecdotal, Personal (1835-1851) – New Series by Garryowen

Chapter XXV : Commerce and Quarantine

Defunct Quarantine Stations 1 – Point Ormond

The first yellow-flagged ship arriving in Port Phillip was the Glen Huntley, from Greenock, with immigrants, on the 17th April 1840. Typhus fever had shown itself on the voyage, and out of 157 passengers there were no less than fifty on the sick list. Great was the consternation amongst the townspeople on the appearance of so unexpected and unwelcome an importation as a probable pestilence, and no time was lost in arranging for the establishment of a Quarantine Station. The then umbrageously picturesque territory, now thoroughly civilised and known as St Kilda, was designated by the Aborigines “Euro-Yroke” from a species of sandstone abounding there, by which they shaped and sharpened their stone tomahawks. Its first European appellation was the Green Knoll, the ominence (then much higher) now recognised as the Esplanade, until Superintendent Latrobe named the country St Kilda in compliment to a dashing little schooner, once a visitor in the Bay. St Kilda was considered a smart walk from town, and adventurous pedestrians made Sunday trips there in the fine weather. About a mile further, looking out in perpetual watch over Hobson’s Bay, was a point known as the Little Red Bluff, afterwards improved into the Point Ormond, and here some four miles from Melbourne, a pleasant enough spot, was organised our first sanitary station, where tents were pitched and crew and passengers sent ashore. Ample precautions were taken to intercept communication with the interdicted world by land or sea, and Dr Barry Cotter, Melbourne’s first practicing medico, not being to full handed with patients in a small, healthy, youthful community, with a magnanimity that did him credit, volunteered his services to take charge of the newly-formed station. There was always a military detachment located here in those times, and from this a guard was assigned to protect the encampment on the land side, whilst the revenue cutter Prince George, from Sydney, then in port, was stationed seaward to shut off any communication by boat or otherwise. The surgeon superintendent entered upon his duties with a becoming sense of their importance. By an amusing perversion of terms he styled the place “Healthy Camp”, and whilst lording it there, issued regular bulletins upon the condition of the invalids and convalescents consigned to his care. Three of the immigrants named Armstrong, James and Craig, died there, and were interred near the Bluff. Their lonely graveyard was afterwards enclosed with a rough wooden railing, destroyed by time, and from oversight or culpable neglect, not replaced, and so the poor mortal remains (very little now), have rested in peace, unprotected, though undisturbed, from their burial day to this.

The Herald, 8 February 1930, p.25

When the Glen Huntley Arrived : Yellow Flag and Point Ormond

by R.J.H.

We must go back to the era of immigration, when new settlers landed on the beach at Sandridge (Port Melbourne), and took their way along the track that led to the encampment on the southern side of the Yarra, for the sad story connected with the Glen Huntley.

She was one of the many immigrant ships, a barque of 450 tons. On October 28, 1839, she put out from Obin, Scotland, and sailed to Greenwich (Eng.), where she remained some weeks. Then the voyage to Port Phillip was resumed. The ship’s immigrant passengers numbered 157. The run to Australia was fraught with uncomfortable incidents, the barque climbing a rock and colliding with another vessel on the way. But, worst of all, so far as the passengers were concerned, was the long confinement and unsuitable fare of their voyage. The ship was badly found, and the resultant misery robbed the migrants of their stamina. And so, with typhoid raging, the men, women and children, who had boarded the Glen Huntley full of high hopes and eager to try their fortunes in Victoria, neared the new land in a weakened condition. Finally the vessel sailed into Hobson’s Bay, the awful yellow flag flying from a masthead.

Fifty people aboard, it was reported, were down with typhus. This was sensational news. An immediate conference was held, and it was decided to fit up a quarantine station at Little Red Bluff (Point Ormond).

The passengers and crew of the stricken ship were hurriedly landed. Dr Barry Cotter rushed to render medical aid, and several women volunteered as nurses. Thanks to the immediate action taken to defeat the spreading of the disease, most of the Glen Huntley‘s passengers lived to prosper in the land of their adoption. But three unfortunates succumbed to the fever and were buried near the station. A fence set to four iron posts was erected around the grave. As the years passed and the enclosure gradually collapsed, leaving the spot unprotected and neglected. Then the encroaching surf threatened to cover the graves. When this was realised it was decided to remove the bodies to the St Kilda Cemetery, and accordingly the remains were re-interred, in 1898, and a memorial stone was erected over the graves.

But the original site – numerous cars whizz by it daily – is barely land-marked. Three of the iron fence supports disappeared, leaving one as the remnant of a kind of memorial. Visitors to the locality have wondered what the lonely post marked. Perhaps it is not there now.

The suburb of Glenhuntley, as well as Glenhuntley Road remain as a reminder of the immigrant ship.

The Australasian, 29 Nov 1930, p.4

First Yellow Flag Ship

by W.H. Hall

Ninety Years ago the barque Glen Huntly arrived in Hobson’s Bay under the command of Captain Buchanan (James Brown, surgeon superintendent), with 157 Government immigrants. She left Greenock, Oban, Argyleshire, on December 14, 1839. She came up to Port Phillip Bay with the yellow flag flying.

On the voyage typhus fever broke out. Eight adults and four children succumbed. There was consternation in the little five-year-old settlement Melbourne was then when it was learnt that about 50 of the newcomers were down with fever.

The Glen Huntly has the distinction of being the first yellow-flag ship to arrive in Hobson’s Bay.

In the Port Phillip Gazette, 1840, this notice appeared:-

Notice is hereby given, that the Glen Huntly, Government emigrant ship, and that infringement of the quarantine laws and regulations will subject the offending parties to the pains and penalties of the same. (signed) A.J.[sic] Latrobe.

The authorities had exerted themselves in a praiseworthy manner to relieve the distress and at the same time restore the health of the emigrants by establishing a quarantine station at the Red Bluff (St Kilda), a projecting point of land. Several cartloads of tents were sent down, and every comfort was provided for the accommodation of sufferers. The disembarkation took place without delay; on Friday, April 24, all the sick had been landed, and by Sunday the healthy had come ashore. One young man died after the vessel had arrived. He was buried on the sands above the high-water mark.

The emigrants in the healthy camp, as far as could be judged, appeared to be a very well-conducted set of people.

On April 30 six new cases of fever had made their appearance; the disease assumed a mild form. Five days later a report was sent to Melbourne that fresh cases had made their appearance, one of which assumed a serious aspect. A week later pleasing intelligence came to hand that eight cases existed and were improving.

Dr Barry Cotter, on May 14, reported as follows:- “I cannot today speak so favourably of our progress here, as, hitherto, fresh cases have broken out in the healthy camp; we have had another death.” (Dr Cotter, who had charge of the healthy camp, died at Swan Hill about 1895. At the first land sale he bought the corner of Bourke and Swanston Street for L30; in 1838 he had a chemist’s shop in Queen Street, near Collins street. He arrived in Melbourne on June 9 1836, by the brig Henry from Launceston.) Another report (May 21) said:- “We are happy to announce that the accounts from the sick camp have been removed to the healthy one.”

From a book kept in the Port and Harbours office, Custom House, Melbourne I made this extract:- “The healthy passengers by Glen Huntly released from quarantine station June 1st, and those sent over from the sick camp to the healthy June 13th and the others June 20 and brought up to Melbourne.” In that black exercise book you may find the names, ages, and occupation of the passengers, also of those who died on the voyage. George Denham, aged 35, succumbed on the day the vessel arrived and was buried above the high water mark. A few years later his grave was covered by the sea.

George Armstrong, aged 48, died on May 4; James Mathers, aged 38, on May 6. Armstrong and Mathers were buried in one grave on the top of the cliff. John Craig, aged 40, May 14, was buried about 3 or 4 ft on the west side of the other grave. These graves were surrounded by a picket fence, which ar=fterwards became rotten. This was replaced by two stone slabs. When the Central Board of Health decided to remove the bodies from the Red Bluff to the St Kilda Cemetery I received an invitation to be present. This took place on Saturday, August 28, 1898, at half past 7am. On the same afternoon a commemoration service was held at the cemetery; a choir, under the leadership of Mr George Andrews, was in attendance and solemnly sang the hymns Oh God Our Help in Ages Past and Days and Moments Quickly Flying, after which Mr Brown, town clerk of St Kilda, read a short history of the vessel and its passengers. Amongst those present were Mrs Bowman (a daughter of Mr Craig) and Mrs McGonagle, who was a girl of 14 on the ship; she died at South Yarra on April 1, 1904, aged 84 years. I had the pleasure of meeting Mr Peter Brisbane, another passenger, who died at Murchison, aged 76 years, on September 26, 1908. Mr David McKenzie, aged, aged 90 years, another passenger, died at Broadford on July 10, 1902. When John Craig left Scotland and the family consisted of himself and five, three sons and five daughters; the youngest daughter, Marion, an infant, died 16 days after sailing from Greenoch, and was buried at sea; the eldest daughter, Mary, a widow, died at Falconer street, St Kilda, on August 15, 1890, about a mile from Red Bluff.

A memorial was erected by public subscription over the remains of these unfortunate pioneers in the St Kilda Cemetery, and was unveiled by the mayor (Councillor A.V. Kemp) on Sunday, April 16, 1899.

A number of letters have appeared from time to time in the papers, some of the writers saying that they were shipwrecked sailors, others that Captain Ormond had command of the Glen Huntly. It was Captain Buchanan’s intention on arrival home to retire from seafaring life, but the call came to him before the voyage was ended. He succumbed to fever and was buried at Cape Town.

Glenhuntly road (Elsternwick and Caulfield) is named after the ship. Point Ormond after Captain Francis Ormond, who arrived here in command of the ship John Bull. 765 tons, from London on January 22, 1840.

[The foregoing article forms part of a paper read by Mr W.A. Hall before the Historical Society of Victoria recently.]

The Age, 21 May 1949, p.8

A Tragic Voyage : Glen Huntly _ Fever Ship

Of the thousands who pass through Glen Huntly daily, few may be aware of the tragic circumstances associated with its name.

The story begins in December 1839, when the barque Glen Huntly, 430 tons, left Oban, Scotland, for Australia. She was in charge of Captain Buchanan, and crammed into her confined space were 157 emigrants, as well as the crew.

Emigrant ships of that time were the subject of much bitter comment by the London newspapers. It was alleged that food was of Inferior quality, that pumps had to be kept going to prevent the vessels, which were badly overcrowded, from sinking. The Glen Huntly was certainly overcrowded, so it is little wonder that eleven migrants died at sea on the way out “from

either smallpox or fever”.

The high hopes of the emigrants approaching their new land had, therefore, been dashed, for it can be imagined that life aboard was anything but pleasant. When the Glen Huntly, on April 17, 1840, finally sailed Into Hobson’s Bay, 50 people aboard were down with typhus, and the dreaded yellow flag flew at the masthead.

An immediate conference was held on shore, and Captain Buchanan was ordered to divert the vessel from Williamstown (the usual anchorage) across the Bay to the Red Bluff, now known as Point Ormond. Several cartloads of tents were sent to form a quarantine station, and disembarkation commenced on April 23.

As Melbourne was but five years old at the time, It can be understood that an acute shortage of medical men existed. However, several women volunteered as nurses, and Dr Barry

Cotter and Surgeon Browne worked untiringly. Two camps had been established — one for the fever patients and the other for the immune — whilst a sergeant and four privates were on

duty to prevent any contact with settlers and others.

On June 5 there were reported discharged from quarantine 50 males, 25 females and 19 children. Others left later, but, although most of the emigrant patients lived to prosper in the

new land, three died and were burled near the station at Point Ormond.

A chain, supported by four iron posts, was erected around the graves, but gradually the sea encroached so far as to threaten to wash them away.

To the north of the kiosk at Point Ormond an old iron post marked the spot until only a few years ago. This replaced the wooden railing that originally bounded the graves. In the presence of about 100 people the graves were reopened on August 27, 1898, and the remains reburied In St Kilda Cemetery.

Public Memorial

In the south-west corner of the cemetery Is to be seen the memorial erected by public subscription to “John Craig, James Mathers and George Armstrong.” John Craig left a wife and seven children. Mathers was a single man and Armstrong a widower. The concluding Inscription on the memorial reads as follows: “This memorial was erected by public subscription to mark a notable event in the early history of the colony. — Glen Huntly Pioneers.”

The barque Glen Huntly returned to Melbourne In 1850, but this time she brought only 46 emigrants in the steerage. She left Melbourne for London on March 6 of that year, and, as far as is known, did not show herself here again. But Glen Huntly-road, as well as the railway station and district known as Glen Huntly, will perpetuate the memory of the stricken emigrant ship.

Memorials

Here is the memorial at St Kilda Cemetery where the remains of those buried at the beach were reinterred

On December 13th 1839, the emigrant ship “Glen Huntly” left Greenock, Scotland and arrived in Hobson`s Bay on 17th April 1840. Many of the passengers suffering from fever were landed at the Red Bluff St Kilda on 24th April 1849. That being the first quarantine station in Victoria.

A few days later JOHN CRAIG JAMES MATHERS GEORGE ARMSTRONG succumbed to the disease and were interred at The Bluff. Owing to the encroachment of the sea their remains were exhumed and removed to the St Kilda Cemetery on 27th August 1898 by the Board of Public Health.

This memorial was erected by public subscription, to mark a notable event in the early history of the colony.

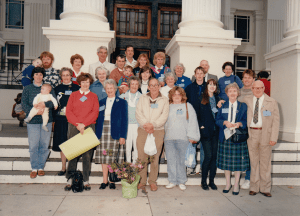

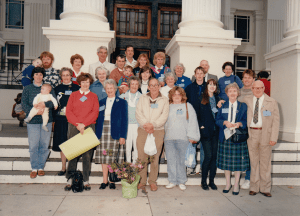

In 1990 a celebration was held by descendants of the Glen Huntly and on that day a cairn was unveiled at Point Ormond to mark the 150th anniversary of the ship’s arrival and Victoria’s first quarantine.

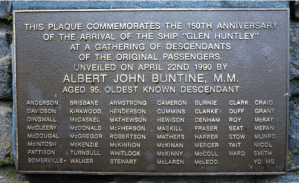

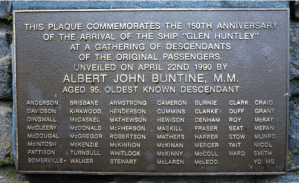

This plaque commemorates the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the ship “Glen Huntley” at a gathering of descendants of the original passengers.

Unveiled on April 22nd 1990 by Albert John Buntine, M.M. Aged 95, oldest known descendant

More about the cairn at Monument Australia >.

After the unveiling of the cairn, a service was held at the St Kilda Cemetery, followed by an afternoon tea at St Kilda Town Hall.